How a Man, a Rat and a Spider Learned to Fly

From NPR

You can listen to a report on this story at:

How a Man, a Rat and a Spider Learned to Fly

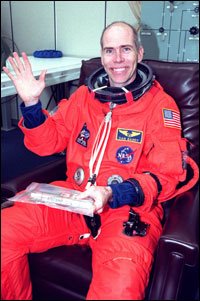

Dan Barry, retired U.S. astronaut, tells the story of a trip he took into space with a rat.

She was a mother rat, part of a scientific experiment. She was placed in a cage with a litter of her babies and when the space shuttle went into orbit and everyone on board became weightless, Barry kept his eye on the rat, wondering how she would adjust.

Barry, who was on his first trip (he would make two more) says that it took the humans the better part of an Earth day to learn to "fly." He had to push himself off from surfaces. If he pushed too hard, he would crash into the opposite wall.

"You start banging your head into stuff," he remembers, "and everybody after the first day has all these nicks and cuts and bruises."

By day two, he was better. By day three, he was, as he puts it, "great at it." He developed routines. He would start with three somersaults, he says, and then "I'm going to land on my feet, I'm going to push off, do three more somersaults, land on my hands. I mean, you're like a gymnast after just a couple of days."

It's Hard to be a Mother in Space

The rat, meanwhile, spent her first day watching her babies float out of the nest and out of reach. She couldn't propel herself toward them, not on the first day when, as Dan puts it, "she kind of flailed around."

But on day two, she got better, and by day three, like Barry, she had adapted to her weightlessness.

"She had it all figured out," says Barry. When a baby would float free she could ricochet off a surface and "take them by the backs of their necks and throw them back into the nest."

The same ability to learn and adapt was observed among spiders, who, on an earlier mission, struggled on the first day with web-weaving, got better on day two and quite inventive as the days went by.

Ignoring Earth-Based Signals

Barry's wife, Susan, is a neuroscientist. She suggests that what may have happened in all these cases is that the creatures gradually learned to ignore signals coming into their brains from their earth-based balance system, called the vestibular system.

"Up in space," Susan Barry says, "the information coming from the vestibular system is not accurate and your brain learns to ignore it and focus much more on visual information."

Dr. Oliver Sacks, also a neurologist and author of the well-known book Awakenings, agrees with Barry's wife, and goes further.

Barry, he says, had to "renounce" his earthly way of doing things.

That, it appears, is what happened to astronaut Dan Barry. When he got a chance to talk to his Earth-bound family, all he could do, his daughter Jenny recalls, is tell them the new moves, turns and spins he had invented for himself.

But what is on display here -- in Dan Barry, the rat and other creatures -- is the extraordinary adaptability of Earth creatures in space, says Susan Barry.

Apparently, our brains and nervous systems are very, very adaptable. More than we knew.

There is, however, an interesting postscript. When Barry returned to Earth, he had trouble readapting. He tells wild tales about trying to move his clothes, even his son around and forgetting that he was back on Earth. (NASA tells astronaut spouses: When he or she gets back to Earth, don't hand them the baby. Not for the first few days.)

But after his second trip, he got better. After his third, he could become an "earthling" in no time at all. It's kind of like Barry developed two brains, says his wife.

"He's got two ways of being," she says. "One that works fine in space. One that works fine on Earth."

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home